Pierce v. Society of Sisters is a landmark case decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1925—100 years ago this year—in favor of Catholic parents and schools against state hostility. This decision, so important but not widely known today except perhaps by lawyers and law students, has had many enduring consequences. Most importantly, the decision protected the continued existence of Catholic schools in the United States—something not to be taken for granted—and resoundingly affirmed parental authority over how their children were to be raised and educated. Pierce recognized these realities as principles of natural law and as fundamental liberties demanding constitutional recognition and protection.

Catholic schools in what is now America predate the American founding by 170 years. The first known Catholic school to open in the present United States was founded in St. Augustine, Florida, in 1606. Maryland—originally a Catholic colony—had Catholic schools operating by at least 1640. The first parish-based school that we know of was opened in Philadelphia in 1783, seven years after the Declaration of Independence and six years before the adoption of the Constitution.

We can see that by the time Pierce was decided in 1925, Catholic schools had been operating in our country for more than 300 years. Next year marks the 250th anniversary of the Declaration, something well worth celebrating; I think it is also worth remembering it will mark the 420th anniversary of the first Catholic school in America.

Catholics were present in America since well before our national War for Independence, but we were here at first in very small numbers. Only one signer of the Declaration of Independence, Charles Carroll of Carrolton, was a Catholic. (He was also the longest-surviving signer.) But Catholics were a numerous enough minority in 1835 to gain the attention of Alexis de Tocqueville, who wrote in Democracy in America that Catholics were “the most republican and the most democratic class in the United States.”

Catholics began to increase in great numbers in the mid-1800s, when immigrants from many countries, principally Ireland and Germany, began to arrive as refugees from not only famine but also political persecution. Italian and Czech Catholics, too, began to arrive in greater numbers later that century. What was on offer for educating their children—a public system remarkably hostile to the Catholic faith—was unacceptable to these new Americans. Catholic schools were not numerous enough to support the new Catholic population, and this prompted a gigantic effort in the Church, especially in the large cities, to establish new schools.

This in turn inspired backlash from the public, a large portion of whom saw Catholics as poor undesirables with anti-democratic tendencies. Many, apparently, did not see Catholics in the same light as Tocqueville had. 19th century America, especially in the cities, was full of turmoil and backlash against Catholic immigration. A prime target for anti-Catholics was the new system of Catholic schools.

There is much more to this whole story, including the successful integration of Catholic immigrants into American society over many decades, but for our purposes we will skip straight ahead to 1925. The Ku Klux Klan was a powerful political and social organization at that time, and not only in the South. They had an outsize influence on Oregon politics as well, and it was at their instigation that the Oregon legislature passed a law that would have required all children age 8 to 16 to attend only public schools.

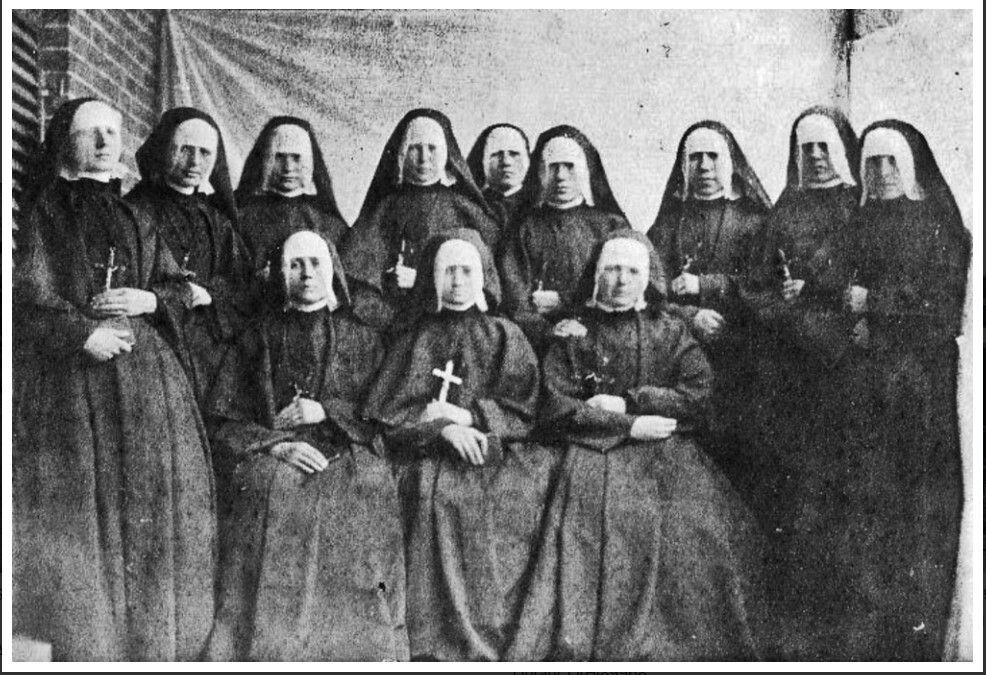

The Society of Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, a Catholic religious order that ran a school system in Oregon, challenged the new law and won a unanimous 9-0 decision at the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court’s short opinion in favor of the Sisters included two important findings:

“We think it entirely plain that the [Oregon law] unreasonably interferes with the liberty of parents and guardians to direct the upbringing and education of children under their control.”

and

“The child is not the mere creature of the State; those who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right, coupled with the high duty, to recognize and prepare him for additional obligations.”

Catholics have never been the majority population, and at various times in our great country’s history, anti-Catholic sentiment has run quite high. If the Court had not ruled in favor of the Sisters, it is conceivable that the Oregon law would have become the blueprint for other states to abolish Catholic education nearly everywhere in the country. As it happened, Catholic education endured and has flourished in many respects in the 100 years since Pierce.

You may recognize that the two lines of the Pierce decision, quoted above, are something of a battle cry even today for school choice. Now, as then, parents have the right and duty to prepare their children for life—that is to say, to direct their upbringing and education.

Long live Pierce, which is still a lodestar at 100 years. And long live Catholic education! At its 420th birthday in America next year, our schools will still be introducing their students to Christ the Lord.